As I walked, the founding question ‘Where do I find myself?’ allowed me to find prismatic points from which to understand the experience. The first of these points was Grief and the second Entanglement. My sense of what I was doing drifted, I became lost, my intentions less dramatic, less heroic, tending, even, towards the pathetic, minus the attendant self-pity. My attention shifted away from wrestling with problems and identifying solutions towards making space for noticing, listening and ‘becoming with’. In short, I was growing a space of care, which is where I found myself setting out for the third time.

Crow

It is early November and the top of Devil’s Dyke is enshrouded in thick fog, the looming tree forms banking steeply off the summit more skeletal now than the last time I saw them only a few weeks ago. I sit on a bench at the head of the dyke and close my eyes, sensing my way back here again. I listen, hearing first the animals, the weather, then people, vehicles and industry less prominently. I reflect that I am developing a practice of listening on this pilgrimage. Making space to listen feels like welcoming in an exiled capacity, a practice of togetherness that weaves me in whenever I allow myself to be still.

When I open my eyes the fog has lifted completely and morning sun glistens on one side of the steep valley. As I stand and lift my pack on, a crow lands where I was sitting and cocks its head at me. As I head off a wild pony makes a beeline for me and stops me in my tracks, gently butting and purposefully nuzzling my chest. Later in the afternoon a roe deer emerges from the undergrowth a few metres in front of me. We remain gazing at each other for a few minutes. Finally I begin to edge closer, until she languidly turns and skips away. We share something that I can’t put my finger on. These interactions feel like manifestations of a different kind of attention.

Mountain

A good friend recently suggested that I treat myself with greater compassion. It’s not a first but this time it lands. When I walk, it’s easier to notice negative thoughts as they emerge; a mindfulness born of movement through the world, to stay for a moment with co-opted modes of self-care. Undermining my efforts towards equilibrium are such regular visitors as low self-esteem, imposter syndrome and cosmic impotence, but the place I get stuck most often while I’m walking is in what I might call outcome anxiety. It’s a kind of mental self-flagellation around the lack of demonstrable productivity in terms of art-making. ‘But what is the work?’ I keep asking myself. I’m certain that it’s very common, especially amongst those who have spent lifetimes in the understanding that to live is to produce results, but are actively engaging themselves in work or practices that foreground the cultivation of care over the generation of measurable results. The writer and mountaineer Nan Shepherd illustrates this difference best in her rejection of the otherwise ubiquitous mountain-conquering narrative via the central impulse in her book The Living Mountain ‘to be with the mountain as one visits a friend with no intention but to be with him’.

Chalk

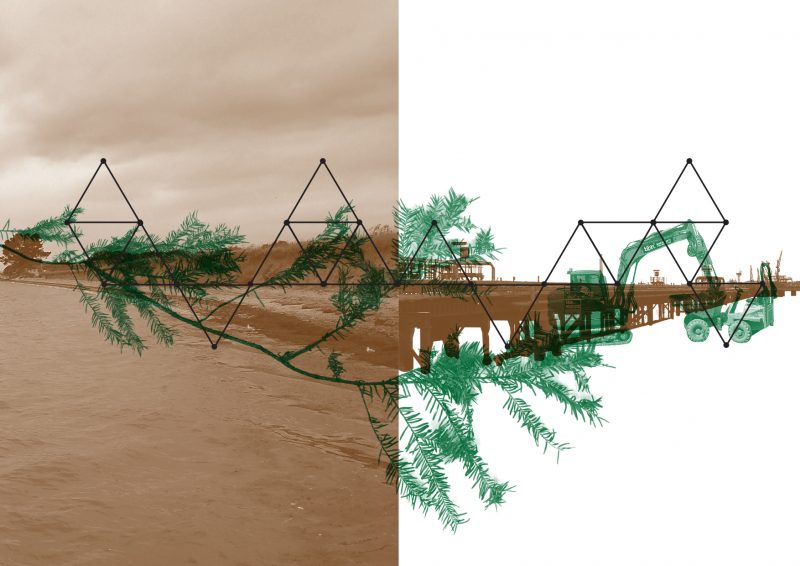

My co-pilgrim and I walk east out of Lewes into a disarmingly quiet rolling chalk landscape. Coming into a small hidden valley called Bible Bottom, where can be found the remains of a Medieval stock enclosure, the landscape seems to fold around us, and a peculiarly deadening silence descends. I sit for a moment and, in the stillness, I can hear my own breath, which reminds of a publication I was reading last night, in which the artist Jade Montserrat uses the beguiling term ‘interspecies respiratory systems’. My own breath hangs in the air, and I fancy that the steep banks of the valley heave almost imperceptibly, at the edge of my vision. I breathe the world in, and breathe myself out into the world. I am held here, I feel genuinely at peace. If we were not walking, we would be moving too fast to sense these places.

Hawthorn

The houses in the manicured villages we pass through have a uniform sense of restraint, even frugality. They are all painted the same colours and feel out of time, dreamlike but also somewhat oppressive. It transpires that they all fall within the Firle estate, from whom they are rented. This part of the world is almost exclusively large estates, woven through with narrow permissive footpaths. The access feels precarious and the atmosphere claustrophobic. Towards dusk our heavy packs are given stony looks by the Barbour-clad occupants of six landrovers, an implied violence I am becoming used to. Long after dark we settle into a small copse high on the downs behind the Long Man Of Wilmington, a seventy metre chalk figure etched into the hillside, and gaze up for hours through gnarled hawthorn branches, from our warm bivvy bags, watching celestial movements. I try to recall other trees whose boughs I have slept under, and how that expression of vulnerability deepens my relationship with the tree into whose care I entrust myself for the night.

Sun

Walking off Windover Hill into Wilmington in the early morning sun, we fall into a conversation about my shifting understanding of this pilgrimage. I’m asked daily why I’m doing it, so I’ve been moulding my answer into shape, for myself as much as to counter the quizzical looks, raised eyebrows and occasionally interesting conversations that I get in response. At the moment my basic spiel goes something like this: the pandemic has made me question many aspects of our culture, and I’ve come to realize that the choices and actions of my life have been dictated by the culture in which I have learnt to be a human in more complex and entangled ways than I had previously understood. I walk so that I might begin to unpick my relationship with modernity, to reconnect with a more ancient version of myself, and maybe to project some of my ancient values into whatever futures may come. I walk to weave relationships of care, to be less complicit in destructive systems. The Navajo writer and teacher Pat McCabe talks about how ‘we think we know what it means to be human, but we only know what it means to be human in a power-over… paradigm’. If conversation comes, it is most frequently about the shortcomings of our culture to deal with a cataclysmic event such as a global pandemic.

I give Co-pilgrim a version of my chat, and practice on him a new bit about the pilgrimage as a ‘walking away from’, rather than a ‘walking towards’, a disinvestment, as Vanessa Machado De Oliveira would say. ‘And towards what?’ he asks, but all I can say for now is that I’m walking away. Maybe we have to become lost before we can find ourselves again.

Branches

On the last day of walking, I cross the halfway point of the whole pilgrimage. The walking feels hard and relentless, and I have run out of energy and after two cold November nights, one on top of a hill and one in a cold church. Also, through bad planning and ill fortune, I have only eaten bread and cheese for three days now. Wishing my foraging knowledge was better, my thoughts turn longlingly towards home comforts.

I cannot shake the uncanny meetings I had a couple of days ago, in which I felt held in the gaze and touch of wild animals in the same way as I experience branches, trunk and roots arching around me as I sleep. Robin Wall Kimmerer writes that it is common in native languages for the word for plants to translate as ‘those who take care of us’ but I am resistant to the idea that we can step out of our centrally heated homes and straight into meaningful kinship without cultivating that relationship. Those ancient parts of me seem to need warming up. It’s common that I experience a deepening of some kind after two or three days walking, which is why it was so strange to have these three encounters almost immediately upon leaving Brighton. Maybe compassion towards myself laid the ground for a wider process of caring? After all, following holobiont theory, self-care could mean to focus ‘my’ efforts on this community of symbiotic microbes that this body happens to be hosting. If so what, ultimately, would be the difference between self-care and care of others, other than size? What then, of that most well-trod of wellbeing clichés; that you can’t care for others until you care for yourself?

Stepping back from that philosophical brink, and adjusting the zoom, it seems obvious that by de-cluttering one’s inner space of the guilt, self-loathing and shame of contemporary digital living that inevitably builds up, deeper engagement with the more-than-human life around us becomes manifestly more reachable. Care becomes an intimate rather than an existential matter. What I wasn’t expecting is the extent to which that care is mutual; not just a growing awareness of what is to be given in terms of stewardship, but also what is received as a form of wild love. Wryly aware that it is only a rampant anthropocentrism that makes such a discovery a surprise at all, I nonetheless feel like I’m removing the dead layers of skin to find something living and connected beneath.