Setting out for the second time, I considered how the journey so far had moved me, and where I found myself as a result. The word which emerged this time was ‘entanglement’.

Body

In early October 2021, I travel back to Chichester on the South Coast, where I finished walking last time. As a series of local trains stutter through the Sussex countryside, I peer out of murky windows, projecting my presence into the landscape. My attention turns inwards, anticipating a temporary retreat from the-world-as-we-know-it. Over the days ahead, I will from time to time notice a sensation that I can only describe as something like the self flowing out into the world, ego dissipating until I sense myself as just another collection of cells, one so-called body jostling up against countless others. As I walk, this osmotic recalibration may at some point reach a critical mass, a becoming-with moment, and I will briefly bask in the ecstatic truth of finding my place in the web of things. Pilgrimage is just my way of getting there.

Stone

Chichester Cathedral houses the Arundel tomb, containing the remains of Richard Fitzalan, 3rd Earl of Arundel and his second wife Eleanor of Lancaster. The stone couple are depicted holding hands, which famously inspired Philip Larkin’s poem ‘An Arundel Tomb’, ending in the line ‘All that survives of us is love’. I cast my thoughts northwards to other groups of pilgrims heading to join COP26 demonstrations in Glasgow at the end of the month. Sentiment from a conversation earlier in the year with writer Sarah Thomas bubbles up to rebuff Larkin. All that survives of us is a planet more healed or more damaged by our presence.

At Boxgrove Priory, the ceiling of the nave is emblazoned with paintings by the early Renaissance painter Lambert Barnard. In each panel, a family coat-of-arms is surrounded and occasionally overwhelmed by tendrils, plants and flowers. I experience, in milder form, the exhilaration of finding a Green Man or Sheela-na-gig lodged in a church’s architecture. These transgressions shouldn’t be in evidence, the church rules out such rampant display. And yet here it is, maybe only visible to the eye that looks for it but there nonetheless, a clear intention towards herbaceous misrule.

Sarah Thomas told me about her experience of living in a stone cottage in a deep-sided valley in the Icelandic landscape. She told me of a raven who, in the winter, would knock on the roof of the cottage for bones, how the raven taught her to be continuous with nature. In this act she transgresses the conditions of modernity, which has us only at war with nature, or as its benevolent guardians. We conquer mountains as phallic hero gestures, raze forests to build cities and flood valleys to provide them with water, and yet I have a growing sense that there are deeper waters to be drawn from in the occurence of a woman somewhere in the world forming a relationship with a raven.

Ash

We spend the night in a railway carriage formerly occupied by a tuberculosis sufferer in the late 19th century. For the second time on this pilgrimage a tawny owl enters my dreams. I wake in the night and go in search of it, wandering through the grounds, lit by a low sodium nightlight casting shadows over a tennis court.

Later in the morning, I’m telling my co-pilgrim Celia about a phrase I picked up from an essay by Helen Macdonald, author of H is for Hawk, who talks about ‘the numinous ordinary – times in which the world stutters, turns and fills with unexpected meaning.’ It interested me because I invariably connect such phenomenological events to place rather than time, and particularly to walking. The Celtic Christian idea of thin places describes loci where we can perceive in close proximity the divine, transcendent, or whatever our version of sacred might be. Pilgrim routes often feel littered with such places.

Celia tells a story relating to a journey undertaken many years ago, cycling to the G8 protests in Germany with two strangers. All three independently felt a strange and dark presence cycling through a forest on the Danish-German border. Shortly after sharing this between themselves they passed a former Nazi prisoner of war camp. She wonders about the balancing possibility of thick places. In the richly ruminative silence that follows, the path opens into a field abounding with birds. Scores of pheasants flap squawking out of the crops, buzzards circle overhead, crows do what crows do, a kestrel lands lazily in a gaunt ash tree.

In the heavy stillness of late afternoon, I drop Celia at Amberley train station, have a quick pint and head to high ground to find somewhere to sleep. The South Downs Way is a narrow corridor of access woven through a landscape of private acreage, vigourously upheld by glowering rangers in land rovers. A lone individual with a large pack heading away from settlements at dusk must be a clear sign of dangerous behaviour, because I am quietly hounded until darkness falls. It is long dark before I find somewhere suitable.

Berries

Even in the scrawny strip of wilderness where I made camp, I wake to find a stirring animality at the edges of my consciousness. Sitting up with brambles in my hair and spiders in my sleeping bag, and munching on a bowl of muesli and berries from the thickets around me, I relish this easy return to a degree of openness and kinship with the more-than-human world. I take comfort in how recent a virus modernity is, enjoying the deep ache of connection that comes with waking under the October sky.

Blood

Each time I take a step, I move through dense networks of relationships with other things. Shifting the weight of my pack, I bend to take a photo on my phone of my boot print in a tractor track, mentally tracing the threads that spin out from that small action into the surrounding woodland, towards the company that make my boots, at least one commercial logging enterprise, the actions of the South African soldier/s who previously owned my rucksack, and all the eruptions of the limitless global techno-industrial complex represented by apps that I have chosen to download onto a small metal device in my pocket. We need another word than entanglement for this dark mirror.

I arrive at Chanctonbury Ring mid-afternoon, too early to stay the night, as I had planned. In any case there is a small herd of longhorn cattle, including a foreboding looking bull, grazing in the same field. I put my pack down for an hour, beckoned in by this place of extraordinary depth and lucidity. Stories about this imposing stand of trees abound, tales of witchcraft, sightings of the Devil, hauntings, brutal histories, layer upon layer of ancient settlement. Aleister Crowley, who lived in the nearby village of Steyning, declared it to be a ‘place of power’. I wander through the curious grove, listening to the place breathe, looking out into the field from this gloomy cathedral. It is a place for becoming fugitive, a place ‘to unlearn mastery, to fall to the Earth, to learn how to commune with soil’ as Bayo Akomolafe puts it. A narrow sanctuary, though, hemmed in as it is by the noisily competing energies of industrial agriculture, aristocratic land theft and corporate blood sport. On my way out my steps phase in and out of sync with the incessant clack of a nearby pheasant shoot.

At dusk, I light a beeswax candle, drink some Irish whisky and gaze back over to Chanctonbury Ring from the top of a bronze age hill fort. I drift off to sleep trying to remember the words to a Wendell Berry poem, as the equinox night wind blows through the small oak above me. Ponies mutter and scratch each other nearby.

Cobweb

I’m woken by a conversation from the other side of the dew-encrusted gorse enclosure I’m sleeping in. I gaze up at shimmering cobwebs and listen to the mansplained benefits of double glazing. My phone has no signal all morning, the immediate world is quiet and mist-laden, and I see not a soul until I reach Steyning. Stopping for a moment in a twisted hawthorn copse, the hubbub reveals itself in all its chirruping, cracking, dripping, rustling magnificence. Even walking through this bustling micro-landscape suddenly feels like a great violence compared to being still. Maybe simply to open oneself to listening is the best way to be in union with other worlds? I struggle for an entry point. I am so often an outsider.

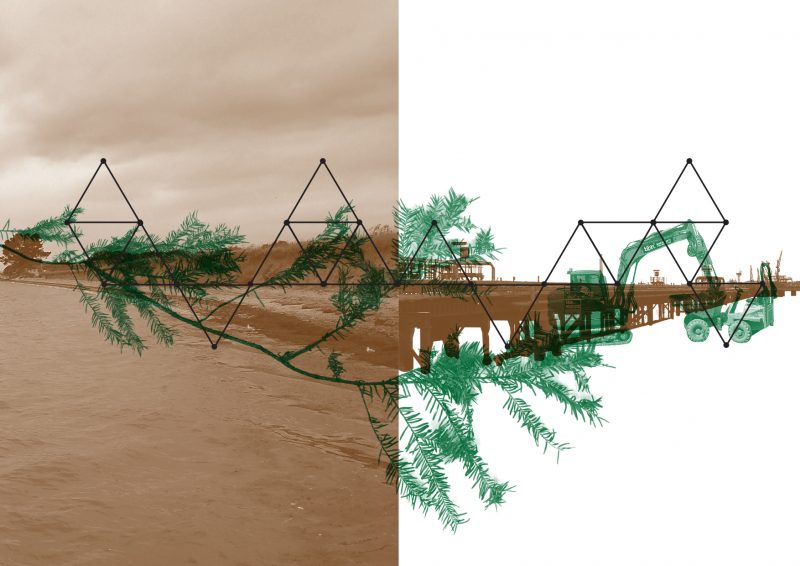

Artist Sabine Popp expresses both the impossibility and necessity of working with the kind of hyperobject that the world presents us with, in her case, the Norwegian coast. She chooses to collaborate with forests of a particular kelp that she calls her ‘hologrammatic’ species: ‘small enough to grasp, but which contains everything: the whole coast, the forests, the marine biologists, the fishes, trawlers and communities and corporations.’ I think about what it means to hold such a wealth of information without the means or desire to broadcast, and conversely, to insist on broadcasting without new information.

Scar

In a thin place, the distance between heaven and earth collapses, but might this not also be true of a thick place? The distance between those seeming poles, how they appear and feel and how we therefore become entangled or ensnared in them, might depend on one’s vantage point. Believing in ascent, we might not notice the earth or our relationship with it. We might even seek to disentangle ourselves from that which appears to hold us down. In seeking thinness, we might renounce thickness, which could be a mistake.

We might find redemption in the more transcendent aspects of soil. We may find that we are interconnected, and that our actions have consequence. We may unearth our attachment to the web of wyrd – the weft and weave of being that extends in all directions. Kneeling down, we may thumb apart the layers of our worlds that focusing upwards has meant we are more likely to tread together. We may begin to discern the difference between the entanglement that comes from being alive in the world, and the ensnarement of living through digital capitalism. There is that layer, too, formed of the opaque scar tissue of human lives, which only the fortunate can sometimes see through.

I take a moment in the autumn sun to try to gather my experiences together, before descending off the South Downs towards the thrum of Brighton. A question that the Scottish writer Alastair McIntosh asked a group of people on a zoom call one dark Sunday evening during the pandemic springs to mind. When we return from the mountain, what remains of that which was learnt on the mountain?

I walk on.